-Elliott Verdier

Listen while you read. Find the “Eternal Child” Playlist here.

Back in July, we spoke about the dangers of conflating our dreams with our fantasies. Our focus then was on how our fantasies affected the wider world. But since any large-scale change begins with the individual, we wondered how fantasy might conflict with our personal lives…

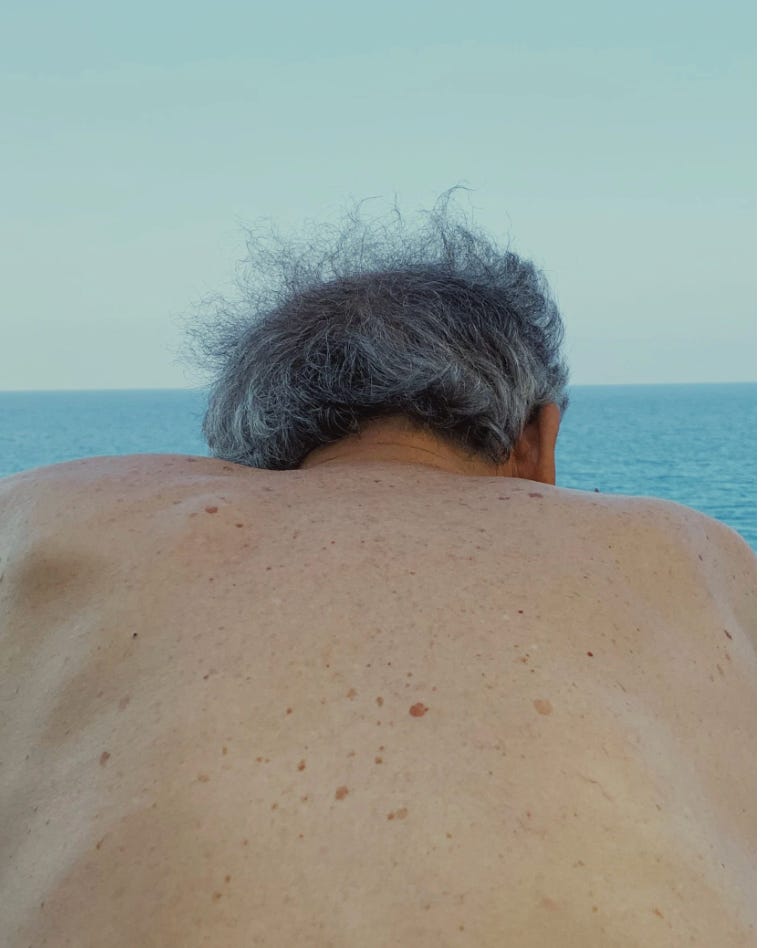

Throughout human history, there has been a clinging to youth. From the legends of a mysterious fountain to an obsession with gold, (which was once prized for its “anti-aging properties”) people have sought the means of eternal youth. But what if this desire to prolong our younger years is coming at a greater cost to us than we realize?

-Osamu Yokonami

It’s become quite common to talk about adulthood as if it were some terrible condition. Who hasn’t heard someone in their life complain about “adulting?” Or, as a child, had an older person try to convince them to resist growing up? At face value, these are just simple jokes, but we’ve likely all heard the adage that every joke has a bit of truth. And it is true. Being an adult is not easy. But what’s particularly difficult is becoming something that was never properly modeled to you in the first place.

Children pick up on a lot. They see and feel things we think we’ve hidden. As children, we learned from our parents and the older folks around us what adulthood approximately was. For some, adulthood meant being angry, judgmental, forceful, or overpowering; for others, it meant being passive, timid, and ineffectual; for others still, it meant responsibility, confidence, self-assurance, and pride; and for some, adulthood was a fun-loving, loose, candy-for-dinner kind of energy. This, of course, is not the limit of what adulthood can mean, but a small sampling.

-Leandro Colantoni

But what children pick up on when they hear an adult utter the words “don’t grow up” is something more like: “The adult world is terribly boring and untenable. You will lose yourself. Resist it at all costs.” And what’s buried in the speaker’s tone, just below the message, is something akin to “I have regrets” or “I’m scared.” None of these things are stated outright but felt in the presence of the speaker. In the way the eyes mourn while a stranger says, “I’m doing well, thanks.” This kind of subversive messaging, the kind that sours the dream of adulthood, has an unfortunate effect on our relationship to maturity as we age.

We already live in a young culture. Ever since advertisers discovered that they could appeal to children to get their parent’s money, we have slowly built a larger and larger section of the economy that revolves around youth. And one thing that anyone would want is to see themselves reflected in the culture. So TV and film, Y.A. literature, ever-evolving toys, and social media platforms are designed as cultural mirrors to capture and commodify the younger generation's attention. But what is missing from this closed circuit is an invitation into adulthood. Instead, we have built feedback loops that perpetuate a sort of cultural navel gaze that never asks the child to rise gradually into maturity. And that’s why this isn’t simply a “youth” problem but an issue with most all of us raised in this context.

We would climb the highest dune,

from there to gaze and come down:

the ocean was performing;

we contributed our climb.

Waves leapfrogged and came

straight out of the storm.

What should our gaze mean?

Kit waited for me to decide.

Standing on such a hill,

what would you tell your child?

That was an absolute vista.

Those waves raced far, and cold.

“How far could you swim, Daddy,

in such a storm?”

“As far as was needed,” I said,

and as I talked, I swam.

-William Stafford, With Kit, Age 7, At the Beach

-Mustafah Abdulaziz

One could say that our whole society suffers from what is casually referred to as “Peter Pan Syndrome.” Carl Jung called it the puer aeternus, meaning “Eternal Boy,” or puela aeternus for the “Eternal Girl.” However, the Eternal Child, generally speaking, “covets independence and freedom, opposes boundaries and limits, and tends to find any restriction intolerable.” From that description, we might see parallels in our own national identity, the very foundation of American cultural values. The Luvenis Aeterna, or “Eternal Child,” is a form of narcissism mirrored abundantly throughout our culture. Put simply, it’s “don’t tread on me.”

Much of what adulthood has meant to many adolescents or young adults is repression. The only people creating any rules tend to be older, and the only people following any rules tend to be younger. From this standpoint growing up is a lot like getting your hand repeatedly smacked away from the cookie jar. So it’s natural then that the repressive regime of age stokes revolutionary tendencies in an age bracket already known for rebellion.

-Thibaut Grevet

But, as Robert Bly wrote in his book, The Sibling Society, “where repression was before, fantasy will now be.” What Bly seems to be getting at is that if we lead with the mind of a child, we will unfairly assess much of our life experience as repressive or restrictive. When a child hears, “No,” when they want to hear, “Yes,” that child might very well describe their situation as repressive, would they know the meaning of the word. In some cases that very well might be the case. But in others, far from it.

We see the prejudicial attitude of youth in great abundance online and in age groups far beyond the spring of their years. One doesn’t need to look long through a comments section or a Twitter feed to find someone overreacting to something. Of course, there are truly offensive things being said on the internet every day. But there are just as many, if not many more benign posts that suffer from over-analysis and needless critique.

-Carlo Piro

But as with all archetypes, the puer/puela has a range of both positive and negative aspects. We can likely intuit what the positives of being childlike are: potential, growth, newness, rebirth, hope, change, and progress, to name a few. But imagine now what some of the negatives might be: selfishness, short-sightedness, greed, violence; a refusal to rise to challenges, or to take responsibility for, or even acknowledge, one's shortcomings–this spells trouble. And if we don’t grow our awareness around how our own personal inner or adaptive child is running the show, we might be part of the problem.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Inner Vision to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.